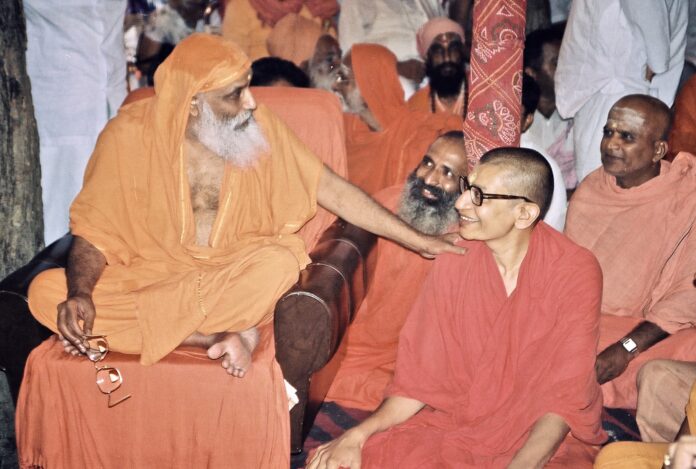

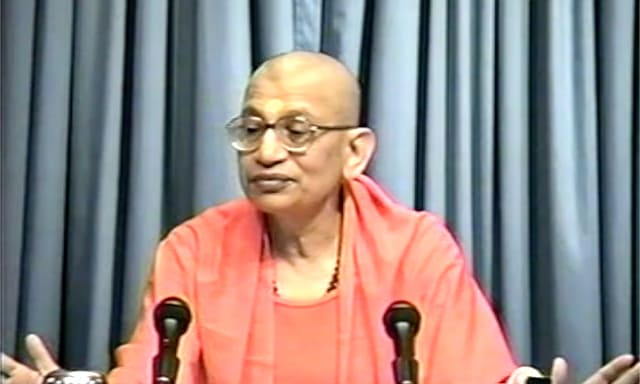

Satsang with Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati

Transcribed and edited by Jayshree Ramakrishnan and KK Davey.

Question:

We seem to fall back into the same rut even after listening to and understanding Vedānta. How should we develop alertness so that we can implement whatever understanding we have?

Answer:

The mind is nothing but the flow of thoughts. Like water, thoughts have a tendency to flow in channels. If there are channels already made in our mind, then thoughts have a tendency to flow through those channels automatically especially if you are not attentive.

One of the reasons why we get distracted, or our mind engages itself in the kind of thoughts that it wants, is what we call mechanical thinking. There is a lot of ‘mechanical-ness’ in our lives. Particularly, when a thing is done repeatedly, we develop a knack of doing it without paying much attention, like knitting, brushing our teeth, taking a shower etc. You don’t have to be paying much attention. One part of the mind does it, while the other part is in some other place. While doing these actions, we can afford to be thinking of something else, even though the body is here and the hands and legs are engaged in doing something. I am able to accomplish these tasks unmindfully.

Similarly, when you take a walk along a regular route, it just takes place. Sometimes eating food just takes place. Drinking tea just takes place. These things take place without us having to pay attention to them. It is something like a camel cart, in a place where they regularly cart things from one destination to another. The camel knows the route and sometimes even travels through the night. Once the camel is on the route, the driver can go to sleep, and the camel will take him to the destination. Our sense organs also are like the camel; the mind is the driver. Having put them on the route, the mind can go to sleep; the sense organs will finish the task. The channels are already drawn, and therefore, our mind flows into the channel of mechanical behaviour. This is acting mechanically.

Sometimes there is also mechanical thinking. We take decisions mechanically just as we do things mechanically. There are some patterns of thinking that are set in our mind. Automatically, we think in a certain way, we decide in a certain routine way. This is mechanical thinking and acting where we are not alert; we are not attentive. Since things can be done without our full attention, we have developed such habits where we are not attentive in many instances. Therefore we need to be attentive to what we do.

Take any one organ, the tongue, for example. Our tongue performs two tasks, that of talking, and that of tasting or eating. The tongue does not eat, but determines what we eat and what we do not. If I like something, I eat it. It is quite possible that I may eat more than what I need. If I don’t like it, I may not eat at all. So it is the tongue that decides what or even whether I eat. There are patterns in talking also. It takes place, and if we are not careful about what we say, things get said. We can start becoming mindful or becoming alert, with reference to the tasks done at the level of the tongue. We decide that we will be deliberate with reference to what we talk and what we eat.

Being deliberate is the way to become free from mechanical-ness. Mechanical-ness comes about when I am not being deliberate and things take place because of the habit. Therefore we have to start being deliberate. There are patterns in talking also. It takes place, and if we are not careful about what we say, things get said.

I decided that I am going to be deliberate in talking. This means that before the word emerges from my mouth, it must have the sanction of my mind as to whether I want to say it or not. This is being deliberate in talking. Lord Krishna talks of how we should regulate our speech. It is called vāk tapas, austerity of speech. In the 17th chapter he says,

anudvegakaram vākyaṃ satyaṃ priyahitaṃ ca yat

svādhyāyabhyāsanaṃ caiva vāngmayaṃ tapa ucyate

Speech, which does not cause agitation, which is true, pleasing and beneficial, and the daily repetition of one’s own Veda, is (collectively) called discipline of speech. [BG 17-15]I become deliberate and make sure that what I say does not create udvega, does not perturb anybody, does not disturb anybody, and does not hurt anybody. Satyam, what I say should be truthful. Priyam, it should be pleasant too. Truth must be presented in a pleasant manner. Sometimes, even when we speak the truth, we are not careful whether we come across as being harsh, or very abrupt. It is possible that it may hurt the person to whom we are saying this. Therefore, not only do I make sure that I do not hurt anybody while speaking the truth, but also that the truth is presented in a pleasant manners.

Manu Smrti says:

satyaṃ bhrūyāt priyaṃ bhrūyāt na bhrūyāt satyam apriyam

priyaṃ ca nānṛutaṃ brūyāt esa dharmah sanātanah

Speak that which is the truth. Speak that which is pleasant. If the truth is unpleasant, may you not speak that! Do not speak pleasantly, which is not true. This is the eternal dharma. [Manu Smrti 4-138]This teaches that we should say only that which is the truth, say it in a pleasant manner, and say it only if it serves some purpose or is beneficial in some way. Only then, should we speak. By following this, I become deliberate. Most of the talking will stop anyway, because a lot of things that we say do not serve any purpose. Sometimes they are not even pleasant. This will also eliminate gossiping, because it does not serve any purpose. Then what should we do with our organ of speech? Svādhyāyabhyāsanaṃ caiva, you repeat God’s name. Repeat stotras. The organ of speech that is given to us can be well utilised in repeating prayers, God’s name. This is called the austerity of speech. Being deliberate in what I say. My organ of speech says what I want to say, and does not say what I do not want to say.

Let us take the other function that the tongue performs: that of eating. I eat what I want to eat, and do not eat what I do not want to eat. A good idea is to decide how much and what I am going to eat before I start eating. Usually idlis and vadās decide how many I eat, not I! Therefore, I decide before they decide. I am going to eat so much. We must be moderate in what we do.

pūrayedaśanenārdhaṃ tṛtīyamudakena tu

vāyoḥ sañcaraõārthāya caturthamavaśesayet

Half of the stomach is to be filled with solid food, one-fourth with liquid food, and one quarter is to be left empty for the movement of air so that digestion can take place. Air movement is needed for the digestion to take place. There is fire in the stomach, which requires oxygen, so there must be space for movement of air. If you fill up your stomach so much that there is no movement of air, then the digestion is difficult. With reference to food, it is also said that we should eat what is hitam, mitam and medhyam. What you eat should be conducive to our health, or hitam. That we should eat in measured quantities is mitam, and medhyam means that which is fit for sacrifice.

Hence, we should eat only that which can be offered to the Gods. This is because God is sitting inside. Lord Krishna says, “I am in the stomach as its digestive fire” [BG 15-14].

Therefore whatever food we eat is really offered to the Lord. And we don’t offer anything and everything in the naivedyam. Medhyam also means pure, sacred. We should maintain that sanctity in what we eat. If we are deliberate with reference to what we eat, when we eat, and how much we eat, then all the eating takes place deliberately. In this manner, we can take a few tasks and perform them deliberately, or with mindfulness. That is the way we cultivate the habit of being deliberate, and being deliberate is a way to overcome mechanical behaviour.

The second kind of thinking is impulsive thinking. We act impulsively. What are the impulses? They are our rāga-dvesās, or likes and dislikes. A lot of our actions take place impulsively and our thinking also takes place impulsively. When I dislike a person, a whole train of thinking takes place based on that dislike. If I like a person, then also, a whole train of thinking takes place as prompted by attachment. Again, become deliberate there, that we do not come under the sway of our attachments or aversions, but think that which is proper. For that, the method is known as pratipakùa bhāvanā, or, taking the opposite standpoint.

Whenever a negative sentiment arises in my mind, I make an effort to replace it with a positive sentiment. When anger or hatred, for somebody, arises in my mind, it will determine what I think, and a whole storm will take place or a whole surge of thinking will take place. Do I put a stop to it? No, rather, I deliberately take the opposite stand. I look for something, about that person, which is likeable. If there is anger, resentment, hatred or dislike, the opposite pakùa or side is forgiveness. What happens is that our mind only looks at only one aspect of something and keeps on dwelling upon that, while overlooking the other aspect. We make our mind deliberately see the other aspect also.

Every coin has two sides. Like that, everything, and every person also has two aspects. If we make our mind see the other side, it will be free from that impulse which has taken over the mind, by its preoccupation of judging the person by adopting one point of view. Thus we should be attentive to see that our mind is not taken over by an impulse. Otherwise it will be the impulse, which will determine our thinking as well as our action. These channels of likes and dislikes are already created, and if we are not attentive, the mind has a tendency to go along these channels automatically. If I dislike a person, when the mind starts thinking about that person, negative thoughts begin to build up and I get very angry even though the person may not be there! The opposite is true too. When I like somebody, the mind keeps building upon itself as well. This kind of buildup of thoughts, which is determined by our impulses, also comes in the way of our being attentive, alert or our being with the realities of life.

Being alert means being with the realities of life. Sometimes realities are bitter and sometimes they are sweet. That is ok. Sometimes they are favourable and sometimes unfavourable. Whatever it is, our mind should be with reality, and not with the projections. Attachment and aversion both involve a lot of projections. By being attentive, and by pratipakùa bhāvanā, releasing the mind from the impulses that may have overcome it, we will again become deliberate and attentive. The third reason why we get distracted is a lack of direction. Sometimes the mind does not have any direction at all. Life sometimes does not have direction and therefore, the mind does not have direction. We are not clear about what it is that life is meant for or what it is that we want to do in our life or even whether there is some objective or some goal in our life. If our life is not systematically directed to the achievement of the goal that we have, then the mind keeps on going from one thing to the other. Quite like a monkey that jumps from one branch to the other, our mind keeps on jumping aimlessly.

When there is no goal, our mind is not attentive or alert. Provide an aim to the mind. In our life, there must be an agenda, a purpose. Whatever we do, must be a step in the direction of our ultimate goal. There must be a purpose to life. There must be a worthy goal, one that keeps on inspiring me for all the time to come. We have short-term goals, no doubt, such as painting the house, doing the basement, etc. All of that is ok.

But all of these tasks that you perform must fall in line with an overall goal. Our day-to- day activities should contribute to what we ultimately want to be, in some way or the other. When that manner of direction is there, we become attentive. With each task that I do, I should ask, “Does this have any relevance to my life? Is it in keeping with my agenda? Does it contribute to what I want to achieve?” Every task that I do will then have the sanction of my deliberating mind. So there are three things we have to consider. One is mechanical thinking. The second is doing things impulsively. The third is doing things aimlessly. Whenever our mind goes along any one of these paths, it tracks its own course. It does not require us.

Then we are not even aware that the mind is on its own and wandering. It is after some time that we realise it, recover, and bring it back. One good way of developing alertness is by doing japa, repeating the name of the Lord. We must be very deliberate there. We must know that the purpose of the japa is to become deliberate. If for instance, you take om namaḥ śivāya, some people want to do a certain number of mālās of om namaḥ śivāya, and their attention is on the number of mantras that are chanted. That is ok. You can do that. But assign some time to do japa, without any goal of finishing any predetermined number. Be committed to reciting every mantra mindfully; be aware of every letter of om namaḥ śivāya. It does not matter how long it takes. But you are aware of every letter of that mantra. Let the mantra be repeated consciously. Avoid a very long mantra because it becomes difficult to pay attention to every word. Japa is good for developing alertness. If the mind wanders, guide it back. If the mind gets distracted, bring it back. This way we become observers of our Mind. Typically, we do not pay attention to our minds, and therefore, the mind does what it wants to do. In japa, we give it a certain purpose, a certain task, and therefore, we can engage the mind in a purposeful way. Japa is a task wherein there is a purpose.

Therefore we can be alert and make sure that the mind only repeats that. Even if it gets distracted, bring it back. This will help us to cultivate the ability to observe the mind. Even if it runs away, bring it back; don’t run along with it. As soon as I find that my mind is distracted, I bring it back. Since I am chanting the Lord’s name, it is healing as well. An association with the Lord is very healing to the mind. So it heals, as well as gives me the practice of being alert. Prāõāyāma and yogāsanas also help. Sometimes, we do these things very mechanically as well. Therefore, before starting, tell yourself that you are going to be attentive. Pay attention to every moment, whether it is while doing āsanas or prāõāyāma.

If we perform these practices of alertness and the mind cultivates the habit of being alert, that alertness will be useful to us elsewhere, while doing other tasks as well. Our time and energy should be utilised in a proper way. Otherwise there is a lot of wastage of our mental energy and time. In being alert, both can be conserved and utilised properly. The ultimate alertness is the awareness of ahaṃ brahmāsmi, I am Brahman. It is called nididhyāsanam in Vedānta. I know that I am Brahman, but my old habit of taking the body to be the Self comes back again and again. So I try to be alert to my true nature. That is ultimate alertness.