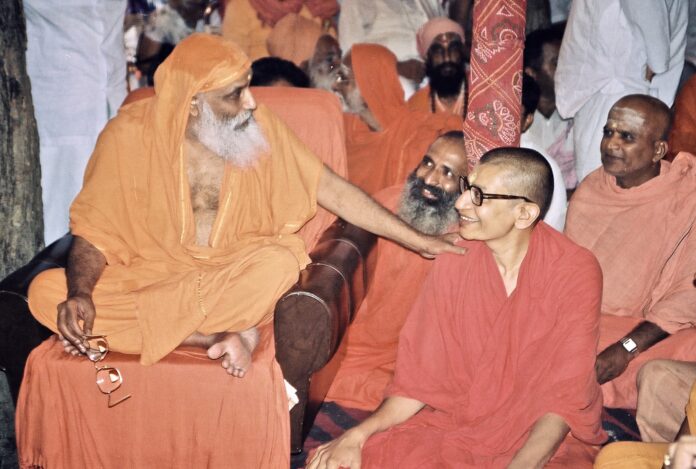

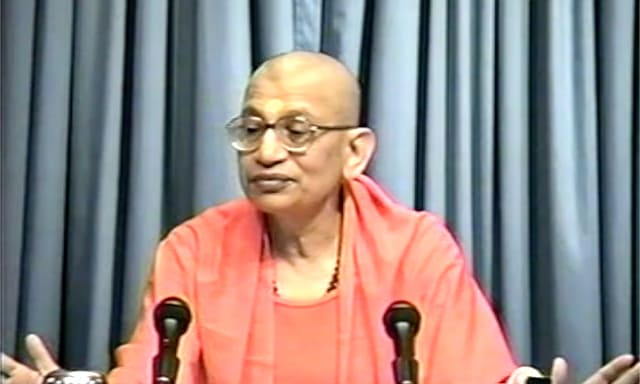

Satsang with Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati

2002 Summer Family Camps at Arsha Vidya Gurukulam, July 2002. Transcribed and edited by KK Davey with assistance from Dr. Martha Doherty.

Question

What is the meaning of the word dharma?

Answer

The word dharma is derived from the root, dhr, as in dhārane, which means to sustain or to uphold. By definition, ‘dharati iti dharmah’, or, that which upholds is called dharma. But then, that which is upheld is also called dharma, as in ‘dhriyate iti dharmah’. When dharma is perceived as that which upholds, it is, in a sense, what we seek. When perceived as that which is upheld by us, as in a way of life, it may be seen as the means. Whatever is to be achieved is called dharma and the means of achieving it is also called dharma. Thus the word dharma can be interpreted both, as being an end, as well as the means.

What is it that sustains? The ultimate cause of the whole universe is asti bhāti priyam or sat cit ānanda or satyam jñānam anatam Brahma. This is the essential meaning of the goal or dharma. Life is therefore lived, in keeping with this fundamental law of dharma, which recognizes that everything is Brahman. The cause upholds the effect, and Brahman being the material cause, nothing is apart from Brahman, just as a pot can never be apart from clay that informs it. This is the fundamental law. As satyam jñānam anatam, He is the fundamental law itself because He is everything. Thus, when we say that there is order in the universe, the ultimate order is Brahman in as much as Brahman, through māya, manifests as this universe.

This order is the law that upholds the functioning of the entire universe. We appreciate the manifest form of this order in terms of omniscience, in terms of fairness or justice and in terms of keeping everything together. This is the saguṇa Brahman. Following this law in our life would be living a life of dharma. That is why the fundamental values of yama (restraint), ahiṁsā (non-injury), satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), brahmacarya (celibacy), aparigraha (non-acceptance of gifts), amānitvam (absence of self-worshipfulness) and adambhitvam (absence of pretence) etc., are taught.

All of them mean only one thing. If you analyze them, they are the recognition of Brahman. For instance, when you analyze non-violence, or truthfulness, you find that they culminate in an order of life that sustains the entire universe and keeps it in harmony. This ultimate truth is Brahman. So the harmony that obtains in the universe is the meaning of dharma, or of any value. Therefore when we lead a life, which is in keeping with the values, it becomes a life, which is in keeping with the fundamental law of life and there is harmony.

There is harmony where there is dharma and there is disharmony where there is violation of dharma. Harmony is our being true to our own nature. The satyam, jñānam, anatam is not out there; it is our own Self. So living a life of dharma is living a life in harmony with our own nature. Whenever we violate dharma, we are violating harmony and in this way violating ourselves, and it becomes stressful. Any stress can be traced to violation of dharma, which is a violation of fundamental harmony. The answer to all stress management is to live a life in keeping with dharma.

It is not easy to live a life in keeping with dharma or the values, if the goal itself is not in keeping with dharma. The goal must be dharma, and then alone is it possible to live by the means, which is dharma. It is possible to live a life of dharma only if the goal is Brahman, if the goal is the Lord, if the goal is the Self or if the goal is wholeness, or mokṣa. Because living a life of values is not easy, to let go of many things that adharma can bring us, is not easy!

Compromising our values can often appear to be quite beneficial. By compromising truth or by violating somebody, you can perhaps benefit in terms of the material gains of artha and kāma, or wealth, prosperity, name, fame, etc. Therefore in order for us to follow the values, it becomes necessary to overcome temptations of these benefits. There is a natural temptation for wealth and there is a natural temptation for recognition. These are acquired values. Growing up, we observe our society valuing these values, and therefore we also place a value upon these things. If these remain the goal of our life, it is very difficult to follow dharma.

Ideally, one can follow dharma when mokṣa is the goal of life. Then, there is no difficulty in letting go of anything. All that it amounts to is neti neti; let go, let go. In living a life in keeping with this dharma, we cultivate the values of viveka (discrimination), vairāgya (dispassion) and śamādi-ṣañka [The 6 qualifications beginning with śama are: śama (control or mastery over the mind), dama (control of the external sense organs such as they eyes, etc.), uparama or uparati (strict observance of one’s own dharma), titikṣā (endurance of heat and cold, pleasure and pain, etc.), śraddhā (faith in the words of the guru and in the Scriptures), samādhānam (single-pointedness of mind)]. There are conflicts in life when we try to follow these values, even while our goal is not dharma. If Brahman or dharma is the goal, and if prāptasya prāptihih, meaning acquiring that which is already acquired, is my goal, it is clear to me that nothing else needs to be acquired. Only then do I realize the value of following these values.

Tyāgenaike amrtatvam ānaśuh [Kaivalyopanishad, 3], it is by tyāga or renunciation that immortality is gained. Immortality is my nature, which is however concealed by false notions. It is concealed by the likes and dislikes owing to these false notions, and it is concealed by the temptations born of these false notions. Giving up the temptations is giving up these false notions. It is the uncovering or removing of the veil, which covers my true Self. Life should become a process of letting go of that which is an obstruction to my owning up to my true Self. Therefore life should become a process of letting go of those obstructions. On the other hand, when life becomes a process of acquiring, we keep on acquiring more obstructions. As the whole scheme of what Vedānta teaches becomes very clear, we develop an appreciation for the values and can live by them. Conflicts and stress will then disappear.

Doing prānāyama and yoga without this fundamental shift in values, does not help much. Stress is basically a spiritual problem, which is not centered on the non-Self; it is centered on the Self. Therefore there must be a spiritual solution. It is not a problem with some chemicals! We may live such a stressful life that it becomes a chemical problem or a pathological problem, but that is a different matter. Stress stems from not understanding the fundamentals of life, not understanding the goal of life, or even having wrong goals.

If artha and kāma, wealth and prosperity, or name and fame are the goals, dharma gets compromised. This is why dharma is placed first among the puruṣārthas. They are dharma, artha, kāma and mokṣa. May you acquire artha and kāma on the basis of dharma! Therefore, dharma is a way of life.

The Vedas also teach you viddhi and niṣedhaþs, the do’s and don’ts, which are essentially dharma. The Bhagavad Gītā begins with the word dharma and ends with the word mama. Some people say that the Bhagavad Gītā teaches us mama dharma or my dharma. The Bhagavad Gītā, then, teaches us dharma in both senses: Brahma vidyāyām and yoga śāstre. It teaches Brahma Vidya, which is dharma in the sense of satyam, jñānam, anatam Brahma and also yoga śāstra, which is dharma in terms of living a certain way of life. So the first dharma is a view of life, which is called Brahmavidya and the second dharma is a way of life, which is yoga śāstra, or mama dharma.

Dhar is the first letter of the first word dharma and ma is the last letter of the last word mama. Sometimes these first and last letters of the text of the Bhagavad Gitā are combined, to give the same meaning. Combining them, you again get dharma. This is arrived at, in the manner of the Paninian Sutras. Panini uses the methodology of ach, meaning all the letters that occur in-between the a-kara to the cha-kara are included in ach. Similarly whatever falls in-between the ha-kara and the la-kara, is included in hal. So also, in the Bhagavad Gītā, dhar is the first letter and ma is the last letter, and thus the entire Bhagavad Gītā is included in dharma.

Śrī Śaṅkarā says, in his introduction to the Bhagavad Gītā, “dvividho hi vedokto dharmaþ, pravṛtti lakṣana, nivṛttilakṣaṇaśca”. The Veda teaches us a two-fold dharma, one being pravṛtti, a striving for something, and the other nivṛtti, or getting rid of something.

loke ’smin dvi-vidhā niṣhṭhā purā proktā mayānagha

jñāna-yogena sāṅkhyānāṁ karma-yogena yoginām

The pursuit of knowledge for the renunciates and the pursuit of action for those who pursue activity. [Bhagavad Gītā 3-3]

Sānkhyā yoga means a life of contemplation. Karma yoga is the life of activity, or rather, a life of devotion leading ultimately to a life of contemplation. Karma yoga is not merely performing karma. Karma, when performed in the spirit of devotion, is bhakti. The first stage is bhakti and the second stage is jñānam.

May you look upon the universe as God! If you look upon the universe as God, then what is your relationship with the universe? I am a devotee, and God is the one to whom I am devoted. Therefore the relationship is such as between the bhakta and Bhagavān. Sva karmanā tam abhyarcya [Bhagavad Gītā 18-46], worship that Lord who is manifesting as the whole universe, through your own karma. This is how karma yoga becomes a worship of the Lord with a bhāvanā that the universe is nothing but that Lord.

The bhāvanā comes first. It is a certain attitude that we entertain in our minds. For example, we are told to look upon all women as Mother. This is a bhāvanā. All women are not related to me as Mother but I look upon them as Mother. This bhāvanā must be in keeping with reality. If the bhāvanā is not in keeping with reality, it will not culminate in reality. So if the bhāvanā is that everything that exists is the Lord, this worship becomes a reality. Then it becomes jñānam. You can acquire this jñānam provided that you start with the right attitude. The yoga of attitude leads to the yoga of knowledge.

Question

Is dharma absolute or does it need interpretation?

Answer

In any given situation we should do what we need to do. Let us take the example of Lord Rama. He is severely criticized for his abandonment of Sita. How do we explain this? After all “Ramo vigrahavān dharmaha’, he is the embodiment of dharma or righteousness. How could he justify doing that? Rama had many roles to play, such as those of a king and husband. On the one hand, his subjects were criticizing him for keeping Sita in his home. Whether the criticism was right or wrong, this is how it was.

On the other hand he had his duty as husband to his wife. If he played the role of a husband knowing that his wife is chaste, and ignored what his subjects said, then he would not be pleasing them. “Ranjanāth rajaha’, or the one who pleases his people, is called raja or king. Thus, if he wanted to make his wife happy, he had to make his subjects unhappy, and if he wanted to make them happy instead, he had to make his wife unhappy. So he had two conflicting demands.

In fact this happens to all of us. There are many conflicting demands in our life. For example, Pujya Swamiji is teaching a course to 100 students and somebody invites him to give a talk for 2 days. Should he go or not? If he goes to deliver the talks, what happens to the students attending the course? If he doesn’t go, what happens to the other people? One has to make a decision. This is where the interpretation of value comes in.

Even though there are universal values, e.g., “I should not do unto others what I do not want done unto me”, these rules need to be interpreted in every situation. Dharma always depends upon time, place and condition. Lord Rama interpreted that his duty or demands as a king was more important than his duty as a husband. You can fulfill the demand that you consider most important in a given situation. For example, when you are at work, your duty as an employee becomes more predominant than your duty as a father. When you come home, your duty as a father becomes more important than your duty as an employee. Thus you will have to determine what, in a given situation, the most important role for that situation is.

There is no general rule about it. This is where we have to use our sense of judgment. We can be wrong, but then we can learn. But at least we would have tried to do our best and been sincere. If we are sincere, in time, we will learn whether we were right or wrong, because the result will reveal it.

Question

But Rama could have gone out and explained to his subjects!

Answer

Yes, he did that. It seems that he sent all his people around. Nobody is fond of abandoning his wife! Do not think that Rama abandoned his wife. He abandoned

himself. Nobody sees that. He never lived in the palace again. From that point on, he lived the life of an ascetic. If Sita lived the life of an ascetic, so did Rama. He never enjoyed the pleasures of a king from that point on. The point here is that there are always conflicting demands upon a person.

Question

Can a person play two roles at the same time, in a given situation?

Answer

You cannot play two roles at the same time. You can play only one role at a time. You can play the other role the next moment. At each moment, however, you can play only one role. Therefore, you should use your judgment.

Question

Are you saying that dharma is relative and not absolute?

Answer

Following dharma always requires us to take into account the particular conditions of time, place and situation. Therefore, there cannot be an absolute rule. Satyam or truthfulness is an absolute dharma. But what truthfulness is, will be determined by the situation. Non-violence is a universal value. But what non-violence is, in a given situation, will have to be determined by the situation.

Question

Was Robin Hood practicing kauśalam in his actions? Is robbing the rich to help the poor kauśalam?

Answer

Dharma is kauśalam. Following what is right and fair is kauśalam. It is possible that some peculiar condition can justify some things. But you cannot generalize from that. We cannot say that it is the right thing to do.

Question

Where do vāsanās come from?

Answer

Vāsanās are past impressions. Everything that I do creates an impression. When we do something over and over again, and often enough, it becomes a habit. We have inherited all kinds of habits from our past, such as habits of thinking, judging and concluding, as well as certain behaviors. A vāsanā is all these tendencies or habits that have been inherited on account of our having done them repeatedly in the past. So what I do without any deliberation is a result of this vāsanā or conditioning. Thus there is conditioned thinking, conditioned responses and conditioned actions. They are all vāsanās.

Question

Sometimes we are not able to change certain things however much we try. What is the way to get a grip over vāsanās?

Answer

Vāsanās manifest in our life as likes and dislikes, as rāga-dveśas. Likes and dislikes are habitual. I like something habitually and I dislike something habitually. Following dharma or following universal values is a way to overcome this pressure of vāsanās or rāga-dveśas. My tendencies or the habits of my past may compel me to act in a certain way. Before acting, I review and see whether this action is in keeping with the values or not. If it is not, I keep my tendencies under check. This is how we slowly restrain and subdue those tendencies, which may push us away from dharma. There may also be many tendencies in me, which propel me towards the path of dharma. I encourage such tendencies.

This is where we follow the guidelines given by the scriptures in terms of dharma or values. These values give us the guidelines as to what would be a proper way of acting in a given situation. For example, by my commitment to non-violence, I am committed not to hurt others by my words, my actions or my thoughts. I try to follow this as much as I can. Nobody can follow these values in an absolute way, but we do have a commitment to follow them as best as we can.

Question

How do we know what dharma, or the right thing to do in a given situation is?

Answer

Dharma as a value, like honesty and non-violence, has to be interpreted in a given situation. These values are universal but the interpretation is subjective, depending upon time, place and conditions. We face many conflicting situations where we need to interpret what a given value means in a given situation. It is possible to commit mistakes when we interpret these values, as we are limited in knowledge and wisdom. To decide what is right or wrong in a given situation may require a lot of information and wisdom, which we may or may not have. We can only make a judgment based on our best intentions and live by it. We cannot expect to always be right. The result of our actions may not always be in accordance with our intentions. Thus, following dharma is a process of learning. Sometimes our intention may not be to violate dharma, but our judgment of the situation may be wrong. However, we can learn from those mistakes and perhaps be a better judge of the situation the next time.

Question

Why did Arjuna not forgive Duryodhana?

Answer

All actions have to be judged based on the codes of conduct that prevail at that time. The codes of conduct we follow today may not be relevant, say, some 50-100 years from now. Therefore when we talk of what happens in the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata, we have to take into account the laws and codes of conduct that were prevalent then. As kṣatriyas it was the duty of the Pāṇḍavas to protect dharma and those who followed dharma. That was the purpose of the law and that is what a kṣatriya was required to do. Lord Krishna says,

paritrāṇāya sādhūnāṁ vināśāya ca duṣkṛtām

dharmasaṁsthāpanārthāya sambhavāmi yuge yuge (Bhagavad Gītā 4-8)

For the protection of those who are committed to dharma and the destruction (conversion) of those who follow adharma, and for the establishment of dharma, I come into being in every yuga.

The sādhus and people who are on the righteous path must be protected from the wicked. They typically do not have the physical strength to protect themselves.

Duryodhana represented adharma. All efforts were made to avoid the war. Lord Krishna himself went as a mediator and made various offers to Duryodhana. However, Duryodhana did not accept any of them and was unfair in his demands, making the war inevitable. Therefore, the war of Kurukṣetra was fought to protect dharma, rather than to regain the kingdom.