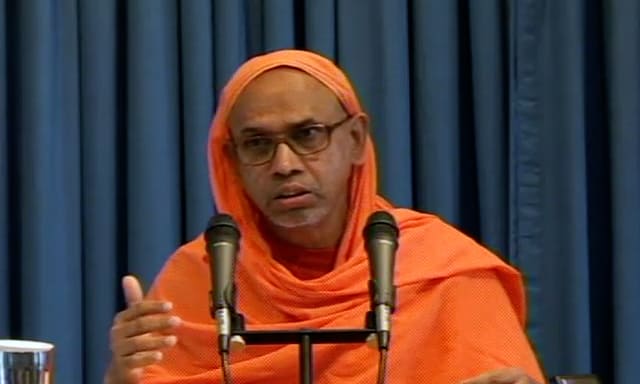

Swami Tattvavidananda Saraswati

(Acknowledgement: Dr. Sri V. Swaminathan)

[Published in the Arsha Vidya Gurukulam 36th Anniversary Souvenir, 2023]

Śrī Lalitā-sahasra-nāma-stotram is recited by many people; not only in India, but everywhere in the world wherever there are even a few Hindus. There are a thousand names in every sahasra-nāma. The reality called Īśvara is nirākāra, formless, and also nirguṇa, attributeless, hence you cannot name the reality in any nāma. To name anything, you need to have some form or attribute or both. But for the purpose of understanding, we appreciate the guṇa- traya attribute of Īśvara manifesting as the form of the entire universe, and we worship Īśvara in a given form.

In this context, the name becomes relevant. An individual has one name. He cannot have more names, except in some situations: in India, for example, we have an ‘alias’ or alternate name. There is no such restriction when it comes to Bhagavān, however, so you may have any number of names. You may have hundred names or a thousand names. In fact, you may have infinite names because any name is nothing but an expression of the Parabrahman. As the Parabrahman expresses in the form of this universe, there are infinite facets to that expression. Based on each one of the facets, you can have a name. Therefore, Īśvara or Bhagavān can have infinite names. In fact, words such as sahasra, thousand, and śata, hundred, have the meaning of ‘infinite.’ This is how we have to understand the word sahasra- nāma. In a given context, however, sahasra-nāma or aṣṭottara-śata-nāma means 1000 or 108 names, respectively.

Among the thousand names, or even 108 names, some of the names are related to mythology. In the context of worship, devotees need three aspects: ritual, mythology, and philosophy. These three aspects put together constitute a devotee’s worship. If the worship has the ritual part of it intact and the mythology is also there (more or less), but the philosophy part is lost or we don’t pay attention to it, that is a big loss. We have to take care that our rituals and devotion based on mythological names and forms are not divorced from doctrinal philosophy. Without the philosophy, the rituals tend to become mechanical and repetitive, and mythological descriptions tend to become superstitious. Therefore, rituals and mythology should always be blessed by the doctrinal philosophy. That is the glory of the Hindu Dharma, in which all three aspects are very nicely synthesized. One can see the beautiful samanvaya, connection, of all the three aspects in the Lalitā-sahasra-nāma.

If you look at the Lalitā-sahasra-nāma, some of the names reflect the rituals that we perform as a part of worshipping Īśvara in the form of the Universal Mother. Many of the nāmas refer to the mythological description of that particular form, namely Lalitā Devī. The Universal Mother has many incarnations as described in Brahmāṇḍa Purāṇa, Devī Bhāgavatam, etc. In some of these incarnations, the Mother has punished many demons like Canḍa, Munḍa etc., and therefore you will find names based on those descriptions. For example, in the Lalitā-sahasra-nāma there is the name Canḍa-muṇḍa-asura-niṣūdinī – the one who has totally dispelled or destroyed the two asuras called Canḍa and Munḍa.

The word asura has to be correctly understood. Generally, we tend to assume that an asura is a rākṣasa. These words are used synonymously, although they have different connotations. We assume that there are some people called asuras, a particular group of people living in some part of the universe, and that they are very cruel and dangerous people. This is a simple assumption. But in reality, we are the asuras – asuṣu ramante iti asurāḥ, those who indulge in sense pleasures are known as asuras. Asuṣu means viṣaya-bhogeṣu, relating to sense pleasures. If we indulge in sense pleasures, in that context we are the asuras. We need not search for the asuras Canḍa and Munḍa.

Once you start indulging in sense pleasures, there is a situation which is favorable and you get attached to that, which is rāga. Now the opposite will automatically be there because the universe cannot exist without the opposites. It necessarily consists of opposites and therefore, once you have a situation that is favorable to you, the opposite situation will be just waiting. You will have another situation that is unfavorable, and you are averse to that unfavorable situation, which is dveṣa.

Rāga and dveṣa, attachment and aversion, are described variously in the mythological stories – as Canḍa and Munḍa in one case, and as Madhu and Kaiṭabha in another. In the context of the philosophy, the meaning is like this: by the grace of the Universal Mother, the rāga-dveṣa in my heart is dispelled and the asura within the heart is gone, so that the deva aspect of me is seen. I am potentially divine, but that divinity is covered by the asura qualities. These qualities are the āsurī-sampat mentioned in the Bhagavad Gītā. The asura qualities cover up the divinity. By the grace of the Mother, the asura qualities are dispelled and the daivī-sampat, divine qualities, are seen; hence the nāma Canḍa-muṇḍa- asura-niṣūdinī.

In this way, many names are based on mythological stories. Every story without exception has doctrinal or philosophical significance. Some names are related to rituals, some are related to mythology, and quite a few names are based on philosophy – karma, bhakti, and jñāna, respectively. Thus, three kinds of names will be found in the sahasra-nāma, which contains a thousand names.

OM TAT SAT